40th Anniversary - Marin Courthouse Rebellion

To the Man-Child, Tall, evil, graceful,

To the Man-Child, Tall, evil, graceful,

brighteyed, black man-child Jonathan Peter

Jackson who died on August 7, 1970, courage in

one hand, assault rifle in the other; my brother,

comrade, friend the true revolutionary, the

black communist guerrilla in the highest state of

development, he died on the trigger, scourge of

the unrighteous, soldier of the people; to this

terrible man-child and his wonderful mother

Georgia Bea, to Angela Y. Davis, my tender

experience, I dedicate this collection of

letters; to the destruction of their enemies I dedicate my life.

George L. Jackson

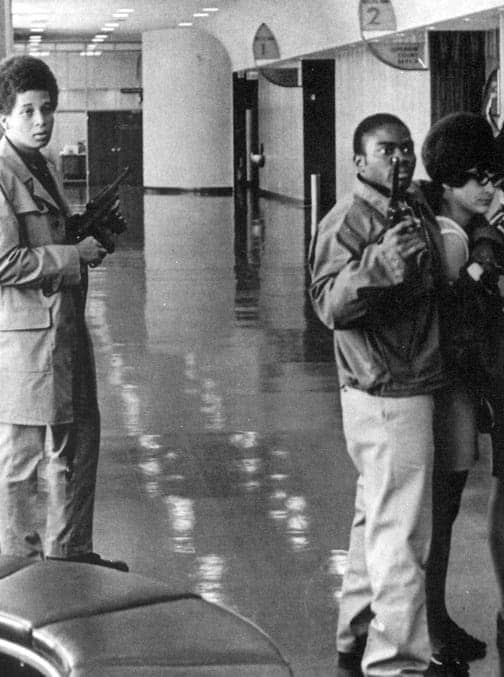

August 7, 1970, just a few days after George

Jackson was transferred to San Quentin, the case

was catapulted to the forefront of national news

when his brother, Jonathan, a seventeen-year-old

high school student in Pasadena, staged a raid on

the Marin County courthouse with a satchelful of

handguns, an assault rifle, and a shotgun hidden

under his coat. Educated into a political

revolutionary by George, Jonathan invaded the

court during a hearing for three black San

Quentin inmates, not including his brother, and

handed them weapons. As he left with the inmates

and five hostages, including the judge, Jonathan

demanded that the Soledad Brothers be released

within thirty minutes. In the shootout that

ensued, Jonathan was gunned down. Of Jonathan,

George wrote, "He was free for a while. I guess

that's more than most of us can expect."

***********************************************

Ruchell Cinque Magee: Sole Survivor Still

by Mumia Abu-Jamal

Slavery is being practiced by the system under

color of law – Slavery 400 years ago, slavery

today; it's the same thing, but with a new name.

They're making millions and millions of dollars

enslaving Blacks, poor whites, and others -

people who don't even know they're being railroaded. -- Ruchell Cinque Magee

(from radio interview with Kiilu Nyasha, "Freedom

is a Constant Struggle," KPFA-FM, 12 August 1995)

If you were asked to name the longest held

political prisoner in the United States, what would your answer be?

Most would probably reply "Geronimo ji jaga

(Pratt)," "Sundiata Acoli", or "Sekou Odinga" --

all 3 members of the Black Panther Party or

soldiers of the Black Liberation Army, who have

been encaged for their political beliefs or

principled actions for decades. Some would point

to Lakota leader, Leonard Peltier, who struggled

for the freedom of Native peoples, thereby

incurring the enmity of the US Government, who

framed him in a 1975 double murder trial. Those

answers would be good guesses, for all of these

men have spent hellified years in state and

federal dungeons, but here's a man who has spent more.

Ruchell C. Magee arrived in Los Angeles,

California in 1963, and wasn't in town for six

months before he and a cousin, Leroy, were

arrested on the improbable charges of kidnap and

robbery, after a fight with a man over a woman

and a $10 bag of marijuana. Magee, in a slam-dunk

"trial," was swiftly convicted and swifter still sentenced to life.

Magee, politicized in those years, took the name

of the African freedom fighter, Cinque, who, with

his fellow captives seized control of the slave

ship, the Amistad, and tried to sail back to

Africa. Like his ancient namesake, Cinque would

also fight for his freedom from legalized

slavery, and for 7 long years he filed writ after

writ, learning what he calls "guerrilla law",

honing it as a tool for liberation of himself and

his fellow captives. But California courts, which

could care less about the alleged "rights" of a

young Black man like Magee, dismissed his petitions willy-nilly.

In August, 1970, MaGee appeared as a witness in

the assault trial of James McClain, a man charged

with assaulting a guard after San Quentin guards

murdered a Black prisoner, Fred Billingsley.

McClain, defending himself, presented imprisoned

witnesses to expose the racist and repressive

nature of prisons. In the midst of MaGee's

testimony, a 17 year old young Black man with a

huge Afro hairdo, burst into the courtroom, heavily armed.

Jonathan Jackson shouted "Freeze!" Tossing

weapons to McClain, William Christmas, and a

startled Magee, who given his 7 year hell where

no judge knew the meaning of justice, joined the

rebellion on the spot. The four rebels took the

judge, the DA and three jurors hostage, and

headed for a radio station where they were going

to air the wretched prison conditions to the

world, as well as demand the immediate release of

a group of political prisoners, know that The

Soledad Brothers (these were John Cluchette,

Fleeta Drumgo, and Jonathan's oldest brother,

George). While the men did not hurt any of their

hostages, they did not reckon on the state's ruthlessness.

Before the men could get their van out of the

court house parking lot, prison guards and

sheriffs opened furious fire on the vehicle,

killing Christmas, Jackson, McClain as well as

the judge. The DA was permanently paralyzed by

gun fire. Miraculously, the jurors emerged

relatively unscratched, although Magee, seriously

wounded by gunfire, was found unconscious.

Magee, who was the only Black survivor of what

has come to be called "The August 7th Rebellion,"

would awaken to learn he was charged with murder,

kidnapping and conspiracy, and further, he would

have a co-defendant, a University of California

Philosophy Professor, and friend of Soledad

Brother, George L. Jackson, named Angela Davis, who faced identical charges.

By trial time the cases were severed, with Angela

garnering massive support leading to her 1972 acquittal on all charges.

Magee's trial did not garner such broad support,

yet he boldly advanced the position that as his

imprisonment was itself illegal, and a form of

unjustifiable slavery, he had the inherent right

to escape such slavery, an historical echo of the

position taken by the original Cinque, and his

fellow captives, who took over a Spanish slave

ship, killed the crew (except for the pilot) and

tried to sail back to Africa. The pilot

surreptitiously steered the Amistad to the US

coast, and when the vessel was seized by the US,

Spain sought their return to slavery in Cuba.

Using natural and international law principals,

US courts decided they captives had every right

to resist slavery and fight for their freedom.

Unfortunately, Magee's jury didn't agree,

although it did acquit on at least one kidnapping

charge. The court dismissed on the murder charge,

and Magee has been battling for his freedom every since.

That he is still fighting is a tribute to a truly

remarkable man, a man who knows what slavery is,

and more importantly, what freedom means.

FREE CINQUE !!

May 27, 1997 © 1997 Mumia Abu-Jamal - All Rights Reserved

****************************************************************

From the Forward to Soledad Brother (1994) By Jonathan Jackson, Jr.

I was born eight and a half months after my

father, Jonathan Jackson, was shot down on August

7, 1970, at the Marin County Courthouse, when he

tried to gain the release of the Soledad Brothers

by taking hostages. Before and especially after

that day, Uncle George kept in constant contact

with my mother by writing from his cell in San

Quentin. (The Department of Corrections wouldn't

put her on the visitors' list.) During George's

numerous trial appearances for the Soledad

Brothers case, Mom would lift me above the crowd

so he could see me. Consistently, we would

receive a letter a few days later. For a single

mother with son, alone and in the middle of both

controversy and not a little unwarranted trouble

with the authorities, those messages of strength

were no doubt instrumental in helping her carry

on. No matter how oppressive his situation

became, George always had time to lend his spirit to the people he cared for.

A year and two weeks after the revolutionary

takeover in Marin, George was ruthlessly murdered

by prison guards at San Quentin. Both he and my

father left me a great deal: pride, history, an

unmistakable name. My experience has been at once

wonderful and incredibly difficult. My life is

not consumed by the Jackson legacy, but my charge

is an accepted and cherished piece of my

existence. It is out of my responsibility to my

legacy that I have come to write this Foreword to my uncle's prison writings.

Today I read my inherited letters often those

written from George to my mother with a dull

pencil on prison stationery. They are things of

beauty, my most valuable possessions, passionate

pieces of writing that have few rivals in the

modern era. They will remain unpublished.

However, the letters of Soledad Brother

demonstrate the same insight and eloquence the

way George's writings make his personal

experience universal is the mainstay of his brilliance.

When this collection of letters was first

released in 1969, it brought a young

revolutionary to the forefront of a tempest, a

tempest characterized by the Black Power, free

speech, and antiwar movements, accompanied by a

dissatisfaction with the status quo throughout

the United States. With unflinching directness,

George Jackson conveyed an intelligent yet

accessible message with his trademark style,

rational rage. He illuminated previously hidden

viewpoints and feelings that disenfranchised

segments of the population were unable to

articulate: the poor, the victimized, the

imprisoned, the disillusioned. George spoke in a

revolutionary voice that they had no idea

existed. He was the prominent figure of true

radical thought and practice during the period,

and when he was assassinated, much of the

movement died along with him. But George Jackson

cannot and will not ever leave. His life and

thoughts serve as the message George himself is the revolution.

The reissue of Soledad Brother at this point in

time is essential. It appears that the nineties

are going to be a telling decade in U.S. history.

The signposts of systemic breakdown are as

glaringly obvious as they were in the sixties:

unrest manifesting itself in inner-city turmoil,

widespread rise of violence in the culture, and

international oppression to legitimize a state in

crisis. The fact that imprisonments in California

have more than tripled over the last decade,

supported by the public, is merely one sign of

societal decomposition. That systemic change

occurred during the sixties is a myth. The United

States in the nineties faces strikingly analogous

problems. George spoke to the issues of his day,

but conditions now are so similar that this work

could have been written last month. It is

imperative that George be heard, whether by the

angry but unchanneled young or by the cynical and

worldly mature. The message must be carried

farther than where he bravely left it in August of 1971.

Over the past twenty-five years, why has George

Jackson not been an integral part of mainstream

consciousness? He has been and still is

underexposed, reduced to simplistic terms, and

ultimately misunderstood. Racial and conspiracy

theory aside, there are rational reasons for his

exclusion. They stem not only from the hard-line

revolutionary aspects of George's philosophy, but

more importantly from the nature of the political

system that he existed in and under.

Howard Zinn has pointed out in A People's History

of the United States that "the history of any

country, presented as the history of a family,

conceals fierce conflicts of interest (sometimes

exploding, most often repressed) between

conquerors and conquered, masters and slaves,

capitalists and workers, dominators and

dominated." U.S. history is essentially that type

of hidden history. Without denying important

mitigating factors, the United States of today is

strongly linked to the values and premises on

which it was founded. That is, it is a settler

colony founded primarily on two basic pillars,

upheld by the Judeo-Christian tradition: genocide

of indigenous peoples and slave labor in support

of a capitalist infrastructure. Although the

Bible repeatedly exalts mass slaughter and

oppression, Judeo-Christian morality is publicly

held to be inconsistent with them. This

dissonance, evident within the nation's structure

from the beginning, informs the state's first

function: to oversimplify and minimize immoral

events in order to legitimize history and the

state's very existence simultaneously.

Ironically, traditional Judeo-Christian morality

is a perfect vehicle for genocide, slavery, and

territorial expansion. As a logical progression

from biblical example, expansion and imperialism

culminated in the United States with the concept

of Manifest Destiny, which held that it was the

colonists' inherent right to expand and conquer.

Further it was a duty, the "white man's burden,"

to save the "natives," to attempt to convert all

heathens encountered. Protestant Calvinism

provided a set of ethics that fit perfectly with

the colonists' conquests. Max Weber, in his

definitive study on religion, The Sociology of

Religion, wrote, "Calvinism held that the

unsearchable God possessed good reasons for

having distributed the gifts of fortune

unevenly"; it "represented as God's will [the

Calvinists'] domination over the sinful world.

Clearly this and other features of Protestantism,

such as its rationalization of the existence of a

lower class,

http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/soledadbro.html#NOT01

were not only the bases for the formation of the

United States, but still prominently exist today.

"One must go to the ethics of ascetic

Protestantism," Weber asserts, "to find any

ethical sanction for economic rationalism and for

the entrepreneur." When a nation can't admit to

the process through which it builds hegemony, how

can anything but delusion be a reality? "The

monopoly of truth, including historical truth,"

stated Daniel Singer in a lecture at Evergreen

State College (Washington) in 1987, "is implied in the monopoly of power."

Clearly, objective history is an impossibility.

This understood, the significant problem lies in

how the general population defines the term;

history implies that truth is being told. It is

an unfortunate fact that history is unfailingly

written by the victors, which in the case of the

United States are not only the original

imperialists, but the majority of the "founding

fathers," dedicated to uniting and strengthening

the existing mercantile class among disjointed

colonies. There can be no doubt that from the

creation of this young nation, history as a

created and perceived entity moved further and

further away from the objective ideal. Genocide,

necessary for "the development of the modern

capitalist economy," according to Howard Zinn,

was rationalized as a reaction to the fear of

Indian savages. Slavery was similarly construed.

The personalization of history, the process by

which we construct heroes and pariahs, is a

consequence of its dialectical nature. Without

fail, an odd paradox is created around someone

who, by virtue of his or her actions, becomes

prominent enough to warrant the designation

"historical figure." There is a leap on the part

of the general public, sparked by the media, to

another mindset. Sensational deeds are glorified,

horrible acts reviled. A few points are selected

as defining characteristics. The media,

conforming to their restrictions of concision

(which make accuracy nearly impossible to

attain), reiterate these points over and over.

Schools and textbooks not only teach these points

but drill them into young minds. Howard Zinn

comments that "this learned sense of moral

proportion, coming from the apparent objectivity

of the scholar, is accepted more easily than when

it comes from politicians at press conferences. It is therefore more deadly."

A few tidbits, factual or not, incomplete and

selective, are used to describe the entirety of a

person's existence. They become part of

mainstream consciousness. We therefore know that

Lincoln freed the slaves, Malcolm X was a black

extremist, and Hitler was solely responsible for

World War II and the Holocaust. All half-truths

go unexplained, all fallacies go unchallenged, as

they appear to make perfect sense to the

everyday, noncritically thinking American. The

paradox has been created: The more famous a

person becomes, the more misunderstood he or she

is. This accepted occurrence is incredibly

counterintuitive: the public should know more,

not less, about a noteworthy individual and the

sociopolitical dynamics surrounding him or her.

This historical mythicization is not, for the

most part, a consciously created phenomenon. The

media don't go out of their way to mislead the

public by constructing false heroes and

emphasizing the mundane. Fewer "dimly lit

conferences" take place than conspiracy theorists

believe. It is the existing political system that

is responsible for the information that reaches

the general public. The state's control of

information created the system, and it

continually re-creates it. Propagated by

schooling and the media, information that reaches

the public is subject to three chief mechanisms

of state control: denial, self-censorship, and imprisonment.

Denial is the easiest control mechanism, and

therefore the most common. If events do not

follow the state's agenda or its ecumenical

ideology and might bring unrest, they are denied.

Examples are plentiful: prewar state terrorism

against the people of North and South Vietnam and

later the bombing of Cambodia; government funding

and military aid to the Nicaraguan Contras; and

support of UNITA and South Africa in the virtual

destruction of Angola, among many others.

Denial goes hand in hand with self-censorship.

The media emphasize certain personal

characteristics and events and de-emphasize

others, in a pattern that supports U.S. hegemony.

The information that reached the public after the

U.S. invasion of Panama in 1989 is telling. It

was not until much later, after the heat of

controversy, that the average citizen had access

to the scope of the devastation. The

effectiveness of self-censorship in this case was

maximized, as the full details of the Panama

invasion were patchwork for years.

While we may assume that the media have an

obligation to accurately convey such an event to

the public, the media in fact perpetuate the

government's position by engaging in their own

self-censorship. Noam Chomsky points out in

Deterring Democracy, "With a fringe of exceptions

mostly well after the tasks had been

accomplished the media rallied around the flag

with due piety and enthusiasm, funnelling the

most absurd White House tales to the public while

scrupulously refraining from asking the obvious

questions, or seeing the obvious facts."

Denial and self-censorship create a comfort zone

for the U.S. citizenry, generally uncritical and

willing to accept digestible versions of

historical personalities and world events. The

reasoning behind denial and self-censorship: do

not make the public uncomfortable, even if that

means diluting, sensationalizing, or lying about the truth.

Ultimately, when denial and self-censorship may

not be sufficient for control of information, the

state resorts to imprisonment. All imprisonment

is political and as such all imprisonments carry

equal weight. Society does, however, distinguish

two categories of imprisonment: one for breaking

a law, the other for political reasons. A

difference is clear: American Indian Movement

leader Leonard Peltier, serving a federal

sentence for his supposed role at Wounded Knee,

is considered a different type of prisoner than

an armed robber serving a five-to-seven-year sentence.

State policy reflects institutional needs. When

the state as an institution cannot tolerate an

outside threat, real or perceived, from an

individual or group, the consequences at its

command include isolation, persecution, and

political imprisonment. All may occur in greater

or lesser form, depending on the degree of threat.

Political incarceration removes threats to the

political and economic hegemony of the United

States. Even though in 1959 George Jackson

initially went to prison as an "everyday

lawbreaker" with a one-year-to-life sentence, it

was his political consciousness that kept him

incarcerated for eleven years. In 1970 George wrote:

International capitalism cannot be destroyed

without the extremes of struggle. The entire

colonial world is watching the blacks inside the

U.S., wondering and waiting for us to come to our

senses. Their problems and struggles with the

Amerikan monster are much more difficult than

they would be if we actively aided them. We are

on the inside. We are the only ones (besides the

very small white minority left) who can get at

the monster's heart without subjecting the world

to nuclear fire. We have a momentous historical

role to act out if we will. The whole world for

all time in the future will love us and remember

us as the righteous people who made it possible

for the world to live on. If we fail through fear

and lack of aggressive imagination, then the

slaves of the future will curse us, as we

sometimes curse those of yesterday. I don't want

to die and leave a few sad songs and a hump in

the ground as my only monument. I want to leave a

world that is liberated from trash, pollution,

racism, nation-states, nation-state wars and

armies, from pomp, bigotry, parochialism, a

thousand different brands of untruth, and licentious usurious economics.

Nothing is more dangerous to a system that

depends on misinformation than a voice that obeys

its own dictates and has the courage to speak

out. George Jackson's imprisonment and further

isolation within the prison system were clearly a

function of the state's response to his outspoken

opposition to the capitalist structure.

Political incarceration is a tangible form of

state control. Unlike denial and self-censorship,

imprisonment is publicly scrutinized. Yet public

reaction to political incarceration has been

minimal. The U.S. government claims it holds no

political prisoners (denial), while any notice

given to protests focused on political prisoners

invariably takes the form of a human interest story (self-censorship).

The efficacy of political incarceration in the

United States cannot be denied. Prison serves not

only as a physical barrier, but a communication

restraint. Prisoners are completely ostracized

from society, with little or no chance to break

through. Those few outside who might be

sympathetic are always hesitant to communicate or

protest past a certain point, fearing their own

persecution or imprisonment. Also, deep down most

people believe that all prisoners, regardless of

their individual situations, really did do

something "wrong." Added to that prejudice,

society lacks a distinction between a prisoner's

actions and his or her personal worth; a bad act

equals a bad person. The bottom line is that the

majority of people simply will not believe that

the state openly or covertly oppresses without

criminal cause. As Daniel Singer asked at the

Evergreen conference in 1987, "Is it possible for

a class which exterminates the native peoples of

the Americas, replaces them by raping Africa for

humans it then denigrates and dehumanizes as

slaves, while cheapening and degrading its own

working class is it possible for such a class

to create a democracy, equality and to advance

the cause of human freedom? The implicit answer is, `No, of course not."'

How does a person inside or outside prison

confront the cultural mindsets, the layers of

misinformation propagated by the capitalist

system? Sooner or later, what can be called the

"radical dilemma" surfaces for the few wanting to

enter into a structural attack/analysis of the

United States. Culturally, educationally, and

politically, all of us are similarly limited by

these layers of misinformation; we are all

products of the system. None of us functions from

a clean slate when considering or debating any

issue, especially history as it pertains to the United States.

George Jackson struggled against the constraints

of denial and self-censorship, to say nothing of

his physical and communicative distance from

society. Political prisoners are inherently

vulnerable to an either/or situation: isolating

silence or elimination. For George, his

vociferous revolutionary attitude was either

futile or self-exterminating. He was well aware

of his situation. In Blood in My Eye, his political treatise, he wrote:

I'm in a unique political position. I have a very

nearly closed future, and since I have always

been inclined to get disturbed over organized

injustice or terrorist practice against the

innocents wherever I can now say just about

what I want (I've always done just about that),

without fear of self-exposure. I can only be executed once.

George was equally aware that revolutionary

change happens only when an entire society is

ready. No amount of action, preaching, or

teaching will spark revolution if social

conditions do not warrant it. My father's case,

unfortunately, is an appropriate indicator. He

attempted a revolutionary act during a

reactionary time; elimination was the only possible consequence.

The challenge for a radical in today's world is

to balance reformist tendencies (political

liberalism) and revolutionary action/ideology

(radicalism). While reformism entails a

legitimation of the status quo as a search for

changes within the system, radicalism posits a

change of system. Because revolutionaries are

particularly vulnerable, a certain degree of

reformism is necessary to create space, space

needed to begin the laborious task of making revolution.

George's statement "Combat Liberalism" and the

general reaction to it typify the gulf between

the two philosophies. George was universally

misunderstood by the left and the right alike. As

is the case with most modern political prisoners,

nearly all of his support came from reformists

with liberal leanings. It seems that they acted

in spite of, rather than because of, the core of his message.

The left's attitude toward COINTELPRO is a useful

illustration. COINTELPRO, the covert government

program used to dismantle the Black Panther

Party, and later the American Indian Movement, is

typically cited by many leftists as a damning

example of the government's conspiratorial

nature. Declassified documents and ex-agents'

testimonies have shown COINTELPRO to be one of

the most unlawful, insidious cells of government

in the nation's history. COINTELPRO, however, was

really a symptomatic, expendable entity; a small

police force within a larger one (FBI), within a

branch of government (executive), within the

government itself (liberal democracy), within the

economic system (capitalism). Reformists in

radicals' clothing unknowingly argued against

symptoms, rather than the roots, of the

entrenched system. Doing away with COINTELPRO or

even the FBI would not alter the structure that

produces the surveillance/elimination apparatus.

In George's day, others who considered themselves

left of center, or even revolutionary, concerned

themselves with inner-city reform issues, mostly

black ghettos. The problem of and debate about

inner cities still exists. However, recognition

of a problem and analysis of that problem are two

very different challenges. The demand to better

only predominantly black inner-city conditions is

unrealistic at best. In the capitalist structure,

there must be an upper, middle, and especially a

lower class. Improving black neighborhoods is the

equivalent of ghettoizing some other segment of

the population poor whites, Hispanics, Asians,

etc. Nothing intrinsic to the system would

change, only superficial alterations that would

mollify the liberal public. As Chomsky asserts in Turning the Tide:

Determined opposition to the latest lunacies and

atrocities must continue, for the sake of the

victims as well as our own ultimate survival. But

it should be understood as a poor substitute for

a challenge to the deeper causes, a challenge

that we are, unfortunately, in no position to

mount at the present though the groundwork can and must be laid.

Failure to understand the radical, encompassing

viewpoint in the sixties led to reformism. In

effect, the majority of the left completely

deserted any attempt at the radical balance

required of the politically conscious, leaving

only liberalism and its narrow vision to flourish.

Nobody comprehended the radical dilemma more

fully than George Jackson. Indeed, he developed

his philosophy not out of mere happenstance, but

with a very conscious eye upon maintaining his

revolutionary ideology. He writes in Blood in My Eye:

Reformism is an old story in Amerika. There have

been depressions and socio-economic political

crises throughout the period that marked the

formation of the present upper-class ruling

circle, and their controlling elites. But the

parties of the left were too committed to

reformism to exploit their revolutionary potential.

George's involvement with the prison reform

movement should therefore be seen as a matter of

survival. Unlike the reformist left, prison

oppression was directly affecting him. His

balanced reform activities improving prisoners'

rights while speaking out against prison as an

entity were required to make living conditions

tolerable enough for him to continue on his

revolutionary path. Simply, he did what he had to

do to survive created space while

simultaneously pursuing his radical theory.

The reform George Jackson did accomplish was and

still is incredible, transforming the prison

environment from unlivable to livable hell, from

encampments that he called reminiscent of Nazi

Germany to at least a scaled-down version of the

like. With his influence, these changes occurred

not only in California, but throughout the

nation. Only now is his influence beginning to

slip, with reactionary politics bringing about

torture and sensory deprivation facilities such

as Pelican Bay State Prison in California, as

well as the reintroduction for adoption of the

one-to-life indeterminate sentence. This type of

sentence is fertile ground for state oppression,

as it is up to a parole board to decide if an

inmate is ever to be let go. A prison can easily

and effectively create situations that transform

a one-to-life into a life sentence. (Tellingly,

the indeterminate sentence is being promoted not

by the right, but by a California senator

formerly associated with mainstream liberal causes.)

Politically, George Jackson provided us all with

a radical education, a viable alternative to

viewing not only the United States but the world

as a political entity. He gave the

disenfranchised a lens through which they could

clearly see their situation and become more

conscious about it. He wrote in April 1970:

It all falls into place. I see the whole thing

much clearer now, how fascism has taken

possession of this country, the interlocking

dictatorship from county level on up to the Grand Dragon in Washington, D.C.

Crucially, George's treatment is a concrete,

undeniable example of political oppression. Race

is more times than not the easy answer to a

problem. Among people of color in the United

States, the quick fix, "blame it on whitey"

mentality has become so prevalent that it

shortcuts thinking. Conversely, stereotypes of

minorities act as simple-minded tools of

divisiveness and oppression. George addressed

these issues in prison, setting a model for the

outside as well: "I'm always telling the brothers

some of those whites are willing to work with us

against the pigs. All they got to do is stop

talking honky. When the races start fighting, all

you have is one maniac group against another." On

the surface, race has been and is still being put

forth as an overriding issue that needs to be

addressed as a prerequisite for social change. In

fact, although it seems to loom as a large

problem, race as an issue is again a symptom of

capitalism. Of course, on a paltry level and

among the relatively powerless, race does play a

part in social structure (the racist cop, the

bigoted landlord, etc.), pitting segments of the

population against each other. But revolutionary

change requires class analysis that drives

appropriate actions and eliminates race as a

mitigating factor. Knowing these socioeconomic

dynamics, George Jackson was first and foremost a

people's revolutionary, and he acted as such at

all times without compromise. His writings

clearly reflect his belief in class-based revolutionary change.

Considering the many structural elements

affecting him, it is easy to see why George and

his message have been misinterpreted. The quick

takes on him are abundant: it's assumed that he

was imprisoned and oppressed because he was

black, because he had publicized ties with the

Black Panther Party and was a well-known

organizer within the prison reform movement.

Although George became a "prison celebrity," a

status that certainly didn't help him in terms of

acquittal and release, ignorance of the actual

forces responsible for his prolonged imprisonment

is inexcusable. The radical viewpoint is

absolutely indispensable when regarding both

George's life circumstance and philosophy. His

life serves not as a mere individual example of

prison cruelty, but as a scalding indictment of the very nature of capitalism.

In these times, there are two very different ways

to be born into privilege. First and most obvious

in the system of capital is to be born into

wealth. Second, and not precluding the first, is

to have an intellectual, politically conscious

base from which to grow as a person

philosophically and spiritually. Radical figures

in modern society Lenin, Trotsky, Ché Guevara,

my father, Jonathan Jackson, and my uncle George

Jackson have the capability of providing this

base through their examples and writings.

Those not born into privilege can achieve a

politically conscious base in different ways. No

veils separate the lower class from the realities

of everyday life. They have been given the gift

of disillusion. Bourgeois lifestyle, although

perhaps sought after, is in most cases not

attainable. Daily survival is the primary goal,

as it was with George. Of course, when it finally

becomes more attractive for one to fight, and

perhaps die, than to live in a survival mode,

revolution starts to become a possibility. Not a

riot, not a government takeover by one or another

group, but a people's revolution led by the politically conscious.

This consciousness doesn't simply appear.

Individuals must grow and work into it, but it's

an invaluable gift to have insight into and

access to an alternative to the frustration, a goal on the horizon.

The nineties are an unconscious era. The

unimportant is all-important, the essential

neglected. What system than capitalism, what time

period than now, is better suited to naturally

create the scape-goat, the seldom-heard political

prisoner, misunderstood in his

cult-of-personality status, held back in a choke

hold from society? It is not only our right, but

our duty, to listen to and comprehend George

Jackson's message. To not do so is to turn our

backs on one of the brilliant minds of the

twentieth century, an individual passionately

involved with liberating not only himself, but all of us.

Settle your quarrels, come together, understand

the reality of our situation, understand that

fascism is already here, that people are dying

who could be saved, that generations more will

die or live poor butchered half-lives if you fail

to act. Do what must be done, discover your

humanity and your love in revolution. Pass on the

torch. Join us, give up your life for the people.

George Jackson

Jonathan Jackson, Jr.

San Francisco

June 1994

No comments:

Post a Comment