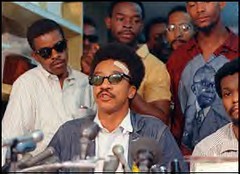

Interview With Karima El-Amin on Jamil El-Amin (Formerly Known as H. Rap Brown)

An Interview With Karima El-Amin on Jamil El-Amin

An Interview With Karima El-Amin on Jamil El-Amin

(Formerly Known as H. Rap Brown)

Pan-African News Wire Aug. 31, 2010

An Interview with Karima El-Amin (Part 1 & 2)

By Nadrat Siddique

The Fourth of July is my birthday. Each year, I

seek an activity which expounds on Frederick

Douglass' renowned musing "What to the Slave is

the Fourth of July" and my social consciousness

as a Muslim. This Fourth, I visited Atlanta to

run the Peachtree 10K race, the nation's largest

10K (it boasts 50,000 participants) and to

interview Karima El-Amin, wife of Imam Jamil El-Amin

(formerly H. Rap Brown).

Imam Jamil El-Amin is one of America's foremost

political prisoners, currently being held at the

infamous high security prison in Florence,

Colorado. I felt his case had received a degree

of exposure, at least by independent Islamic

media, but that far less was known about his wife

and partner in the struggle, an activist in her

own right.

Karima El-Amin graciously granted me an interview

at short notice, even though it meant according

me her scant leisure time (the holiday was one of

those rare occasions on which she closed her law

office). I was to meet her soon after my race.

When I called to confirm the details of our

meeting, she expressed concern for my condition.

Was I too tired and dehydrated after the race,

being unaccustomed to Atlanta weather? And did I

require more time to rest before our meeting? I

was reminded of Imam Jamil, whose self-less

concern for his visitors to the prison even while

he himself was being subjected to daily

humiliation at the hands of prison guards was

fabled. And she insisted she would drive to my

hotel so that I would not have to attempt to

navigate unfamiliar territory. We agreed to hold

the interview in my hotel room.

She entered the room, a slender, bespectacled

woman, with quiet manner and majestic bearing,

dressed modestly in light green hijab. But, as

she began to speak, I realized this was easily

the most eloquent, self-confident, and

politically aware Muslim woman I'd encountered.

She was clearly very seeped in Islamic faith;

indeed, it may have been what allowed her (and

hence her family) to survive the incredible

trials they'd experienced; yet she was not

ostentatious with her Arabic, nor haughty or

judgmental of me or others.

Q: How did you meet Imam Jamil, and what attracted

you to him initially?

I met him July 31, 1967. I remember that day

because it was the first day I had a job. I had

just graduated from the State University of

Oswego. I was there four years. I majored in

English with the aim of teaching K - 9th grades.

Imam Jamil walked into the job. He was staying

with my supervisor. The job was on 135th Street,

in Harlem. It was with Job Corps. I thought I'd keep the job a while.

The Imam walked in. At the time, he had a cadre

of bodyguards. He was meeting Minister Farrakhan,

so he asked the supervisor "See if she'll go to

lunch with us." I was the only female at a big

table of only brothers. I remember it was a big,

big table, and we got back to the job at 5 PM.

That evening, Nina Simone was performing. She had

invited Imam Jamil. In later years, he kept in

touch with her. She autographed a photo for him

that night, which I still have.

Q: Tell me about yourself and your background.

A. My grandmother and mother were Canadian. In

1929, my grandmother brought my mother, her

sister, and one of her brothers to the U.S. after

divorcing my grandfather. They were deported, and

then returned. Then, in 1938, my grandmother went

before a judge to ask for her citizenship. In

1942, while my grandmother was living in Los

Angeles, Immigration denied her case. By 1942, my

mother's sister had married. Her husband was in

the entertainment business, and his father wrote

"Dark Town Strutters Ball." She was a little activist

and traveled broadly.

My mother lived in the building where La Guardia,

Duke Ellington, and other musicians lived on

Fifth Avenue in New York. My father was from the

U.S. (from Virginia), and was in the navy. He and

my mother married in 1942, and I was born years

later in New York.

We moved to Riverton, built and owned by

Metropolitan Life Assurance, in Harlem on Fifth

Avenue. It was built mainly for African Americans

so that we would not reside in the company's

other private developments built for Europeans.

In fact, my mother and father were considering

being part of a class action suit to challenge

the discriminatory practices of the company.

Nevertheless, my parents moved to Riverton where

I went to school in Harlem. and my mother was

involved in the PTA.

My mother was involved in the PTA fighting zoning

issues, and that was the first time the FBI came

to the house. They thought the communists must be

behind this, and we thought they were going to

take our mother away.

My mother is from Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. We

would go back and forth to Canada to visit our

grandfather, our aunts and uncles, and cousins.

My father didn't want to tell a fib, so when they

asked him is everyone in the car a U.S. citizen,

he would just nod his head.

We're actually the descendents of runaway slaves.

My sister and cousins are being tested to

determine where we are from, but so far Spain,

Portugal, and Europe are coming up, and not

Africa. So, my family members still are exploring

further testing.

My mother, after 30 years of being a housewife,

went for a job with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

Thurgood Marshall was the head of it. He wanted

her to be in charge of payroll. To do this, she

had to be bonded. Thurgood Marshall sponsored my

mother to this end. I became the baby sitter for

Thurgood Marshall and various African American

judges and attorneys of the Legal Defense Fund.

I remember that my mother would tell my friends

to put their dresses on so we could go to the

Apollo. During the intermission, she had us walk

around with buckets to collect money for

whichever case was being fought in the South at

the time.

Q: What led to your personal involvement in the

Black Liberation struggle?

In college, I got involved with Friends of SNCC.

That should have told me I'd wind up with the

chair of SNCC.

I graduated in June and met Imam Jamil in July.

My sister and her husband got arrested. They were

with RAM (Revolutionary Action Movement). This

was the first case in which middle class African

Americans were involved in supporting the Black

Liberation struggle.

RAM is mentioned in the original COINTELPRO

papers along with SNCC, Stokely, H. Rap Brown,

etc. My husband went to a rally for RAM before

I met him.

By August 1967, the FBI had contacted me. They

said, "You know your sister was framed. If you

help us, we'll clear her." I told them I knew

she'd be cleared because she was framed. The FBI

wanted me to work for them to provide reports on

Imam Jamil.

My parents were very involved with the community.

We were a close knit family. I had a

non-traumatic childhood (other than the fact that

I was almost electrocuted). We did not go without

anything. We traveled a lot. My father helped

form an organization for African American city

workers in transit.

My first trip to the South was in 1959 when a

girlfriend of mine invited me to travel with her

to visit her relatives. One day, we went shopping

to look at earrings. I went to hand money to one

of the workers, and she threw the money on the

floor. Later, I was trying to buy a hotdog, and

they would not sell it to me, because the hotdog

stand was "Whites Only." Up in New York, we

protested White Castle (fast food establishment).

My mother was very proper. When my husband's book

came out, she would not say the name of the book,

because it was called Die Nigger Die.

The FBI hounded my parents. They went to my

father's job repeatedly. Despite this, my parents

continued to be very supportive. I came from very

smart, compassionate parents. They both died

young (at age 51). One day, we went to the

grocery store. When we came out, we found our car

had a flat tire. We said, "Oh FBI."

Not long after, my father stopped at a gas

station to fix a flat tire. He collapsed and

died. Imam Jamil's mother died the week after

that. Then, my mother went into the hospital.

They discovered an aneurysm on the right side of

her brain. Then, they located another on the

left, and she died two months later, in June.

Then, in October, Imam Jamil was shot and went to

the same hospital where my mother died. In fact,

he was in the room next to where my mother spent

two months before she died. All this happened in

one year. We just didn't have time for grieving.

*************************************************************************

As I listened to Ms. Al-Amin, I was stunned by

the resilience and resolve of the Al-Amins,

undaunted by the challenges before them. Against

all odds, they'd patiently continued a dignified

and peaceful resistance. Most amazingly, they had

not restricted themselves to the challenge of

wrongs done to Imam Jamil, although this was, in

itself, a huge litany. They were tackling the

very constitutionality of laws which violated the

rights of inmates, political prisoners, and other

victims of the prison-industrial complex. In

other words, from behind bars, the Imam, his wife

at his “side,” was fighting to “free the

slave”while many seemingly free imams and others

on the outside cowered in fear and silence.

Q: Tell me about Imam Jamil’s transition from

black radical to mainstream Muslim Imam. Did you

feel you had to influence him to repudiate or

reconstruct that image into a more moderate one?

A: My sister’s first husband was a Muslim from

the Republic of Guinea. I remember they had a

Qur’an on a stand, and they gave us a prayer rug

before we were Muslim that we hung on our wall;

consequently, that was one of our early exposures

to Islam. My husband took his shahada in December

1971, while he was incarcerated in New York City.

Brothers from the Dar-ul-Islam in Brooklyn

entered the jails as chaplains and volunteers to

hold classes on Islam. The transition to Islam

was very natural for my husband because it did

not compromise any of his positions.

I took my shahada a few months later, in February

1972, when Imam Jamil gave it to me. I still was

reading about Islam after he became Muslim

because I wanted to make sure I was becoming

Muslim based on my belief. It was a natural flow

for us to become Muslim. We never felt we had to

explain the transition from his past as H. Rap

Brown to Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin, although the

transition was confusing for those who did not

understand my husband. After El Hajj Malik

Shabazz, my husband was the next public figure in

the Movement to become Muslim. We then saw other

black liberators in the 1970s and 1980s become Muslims.

Q: What made you decide to attend law school?

A: Law was my third profession. Here in Atlanta,

I worked for a 15-year period with two

foundations giving money to grassroots

organizations and working on desegregating public

higher education and enhancing the traditionally

black colleges and universities.I did not go to

law school until 1992, while I was teaching

English. When I was in high school, I considered

law as a career. My mother worked at the NAACP

Legal Defense Fund when Thurgood Marshall was the

Executive Director, and lawyers were dispatched

to the South to represent students and local

people who were being arrested, brutalized,and

killed. This certainly influenced my early

thoughts on considering law. Also, once I married

my husband, I was constantly with William

Kunstler and at the Center for Constitutional

Rights in New York, as he and the organization

represented my husband. And lastly, the fact that

the government was continuing its efforts,

COINTELPRO-style,to incarcerate my husband, was

another factor that moved me finally to attend.

Q: What did you see as your role in the Al-Amin

household?

A: I saw my role as a stabilizing one. I was not

making speeches, and I wasn’t out there in the

public with my husband. I saw my role as

maintaining peace at home. I was a teacher during

our early years of marriage. My concentration was

making sure we could eat together and be together

as a family. It always amazed me when we heard

people gasp and say, “I saw H. Rap Brown, and he

was holding a child,” or “I saw the Rap and he

was holding a cat.” Ordinary things he did

shocked people because the media had dehumanized

him. When things are moving wildly, it’s

necessary to have normalcy at home, so I would

try to maintain a sense of normalcy in an abnormal

world.

Q: What attitude or outlook to life did you adapt

after you realized that your husband would be

locked up for a long time? What has been your

biggest challenge since his railroading?

A: Naturally to be stripped of a husband, a

companion, is devastating. Because I came up

through the struggle with him, I understood the

challenges. Many people refer to my husband as

the “last man standing.” He was a COINTELPRO

target and he has remained one. I understand his

innocence, and the governmental efforts to

silence him throughout a 43-year period. This

gives me the strength to remain strong and by

his side.

My biggest challenge was ensuring that I could

provide for my family in my husband’s absence. I

was doing so many pro bono cases that I realized

that I had to begin charging for my legal

services. I was faced with raising a 12-year old

son, who was very close to his father, and I had

to monitor the psychological impact on him. He

was a basketball son, and accustomed to seeing

his father at all of his games since he was five

years old. I had to move quickly to maintain his

life as a youngster, and I could not miss a

basketball game or school activity. My

overarching challenge naturally wasand continues

to beto work to free my husband.

Q: Has Imam Jamil’s incarceration influenced the

career choices of your children? Do you think

they will go to law school?

A: We have two children: Kairi and Ali. Kairi is

22 and Ali is 31. Kairi is in law school. He is

in his second year, but wants to practice,

perhaps, entertainment/sport or international

contractual law. He graduated from high school

when he was 16, and went to three universities

before graduating, still on time. Kairi was in

the eighth grade when his father was arrested,

and during the trial he would come to court

carrying his backpack. He was a trooper.

Q: Have the children visited their father in

Florence, CO? Tell me about that visit.

A: Kairi and I visit Imam Jamil in Florence,

Colorado. He is being held in the Supermax

prison, 1400 miles away, which makes traveling

very costly. It essentially takes a full da to

travel there and another day to return home. It’s

really been a struggle, and we haven't been able

to visit as often as we'd like. Florence is seen

by many as a concentration camp for Muslim

inmates. Imam Jamil is handcuffed at the waist

behind a glass when we see him in one of the

legal rooms. On the days we are with him, we are

able to visit for approximately six hours. If he

receives food during the visit, he has to hold

his hands chained in front of him in order to

eat. It is a very difficult position, and his

wrists begin to swell.

The law firm now representing Imam Jamil pro bono

also worked on suits for Guantanamo prisoners.

One of their lead attorneys said that if he had

to choose between Gitmo and Florence, he would

choose Gitmo. Imam Jamil is held in solitary

confinement, and Florence is a “no contact”

institution, so the conditions are punitive

and deplorable.

Q: Imam Jamil’s projects to rid the West End

community of drugs are well known, as was his

mentoring of the youth. Have these projects

continued, and what is the extent of your

involvement with them?

A: I’m still involved with the community. It’s a

community I helped start with Imam Jamil and it

is dear to me. Many of our children now are

active in the community, and taking leadership

roles, and it’s wonderful to see and feel their

energy. We have continued with classes, youth

activities, and the Riyaadah that we started in 1982.

Our community under the leadership of my husband

always included the youth in our family-oriented

activities; therefore, mentoring the youth continues

to be a focus.

Q: Do you feel that things have gotten worse in

the city since Imam Jamil was locked up?

A: When he was around, there was some vibrancy in

the neighborhood. We all miss his presence and

his hard work to keep the ills from consuming our

community. We can all agree these are drastic

times for people, and this is reflected

throughout the inner cities. My husband always

reminded people that Islam is the medicine for

the sick; it is the cure for all society’s ailments.

Q: Unfortunately, the number of political

prisoners has increased exponentially since your

husband went to prison. What is your advice to

the current generation of Muslim law students, as

to how they should operate within the U.S.

justice system? What should be their contribution

to the Muslim community?

A: Imam Jamil was instrumental in getting a

Muslim lawyer’s group started. This was similar

to what SNCC [Student Non-Violent Coordinating

Committee –editor] had,where attorneys

represented civil rights workers on a pro bono

basis. We have to get more attorneys who would be

able to take on cases. Many Muslims who are

arrested now have not committed criminal

activities, but are arrested for “thought

crimes.” We need a band of attorneys to be able

to represent Muslims who are being entrapped by

informants. Family members of those arrested are

draining their resources and are receiving

minimal assistance from the Muslim community. We

need to recognize that the divide-and-conquer

strategy is working very well within the Muslim

community, with the result that dissent is

crushed and support for political prisoners is

diminishing. We need activist attorneys to

challenge constitutional violations and the

unjust arrests so that families will not have to

go to court with attorneys who are concerned

only with billable hours.

Q: What is the current state of Imam Jamil’s case?

A: Imam Jamil was convicted in 2002 on Georgia

state charges. He immediately was transferred to

the maximum state prison in Reidsville, Georgia,

where he was held in administrative lockdown.

Despite his physical isolation, his presence in

the prison for other inmates had an electrical

charge. While visiting him, we would see other

inmates, passing by on their visits, raising

their fists or giving salaams, andtheir visitors

would do the same.

In 2006, the FBI released a report called “The

Radicalization of Muslim Inmates in the Georgia

Prison System.” The report focused on the effort

by Muslim inmates in the Georgia prison system to

have Imam Jamil serve as imam over all Muslim

Georgia inmates. Georgia officials realized that

Imam Jamil did not initiate the effort, and

although he agreed to stop the effort, the FBI

launched its own investigation. We believe the

report by the FBI was the final step in getting

him moved out of Georgia, to the federal supermax

prison where so many high profile Muslims are being

held.

The Georgia conviction is still being challenged

through a habeas corpus action to prove my

husband’s innocence. [A writ of habeas corpus is

a request for a reversal of a conviction. Imam

Jamil’s habeas lists fourteen very compelling

reasons why his conviction should be

reversed.–editor]. That was filed in 2005. We are

at the end of that state process, and attempting

to move forward, and hopefully will have a ruling

next year.

Q: So even though Imam Jamil was not convicted on

any federal charges, he was moved from state to

federal custody?

A: Yes, Imam Jamil was moved out of Reidsville

without notification to his family or attorneys.

The move was based on an agreement between the

State of Georgia and the Federal Bureau of

Prisons to take on state prisoners. Georgia pays

the Federal Bureau of Prisons every month to

house him. They whisked him away in a hot van,

and had him sit

for hours in 90-degree temperature until he

developed chest pains, and had to be taken to an

Atlanta hospital. We knew nothing about this.

They kept him overnight, and then returned him to

the airport for a flight to the Oklahoma City

Federal Penitentiary. From there, he was taken to

Florence, CO. The move alone violates the Bureau

of Prisons’ rule that an inmate must be housed

within 500 miles of his home.

Q: Tell me about some of the lawsuits initiated

by Imam Jamil.

A: Imam Jamil filed numerous grievances while in

Reidsville and Florence, Colorado, that

ultimately ended in his filing a lawsuit:

Legal Mail Lawsuit

This lawsuit was filed because the Reidsville

prison staff continued to open legal mail from me

to my husband. The Department of Corrections in

Atlanta was notified that opening his legal mail

in his absence was a violation of the

department’s standard operating procedure, and a

First Amendment violation. The Southern District

Court, in which the lawsuit was filed, ruled in

his favor, and Georgia appealed. The case then

went to the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals for

argument. At that point, the 11th Circuit

appointed a prominent Atlanta-based attorney and

his firm to represent my husband on a pro bono

basis. The 11th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled

that the action of the staff in opening legal

mail from me to my husband was a First Amendment

violation. Georgia appealed to the U.S. Supreme

Court; that Court refused to hear Georgia’s appeal.

Retaliation Lawsuit

From the day he entered the Reidsville Georgia

prison, he was held in administrative 23- hour

lockdown. He’s never done a juma’a since he was

incarceratedfrom 2002 until now. So, we do have

fundamental constitutional issues. We will

continue to challenge the inhumane and punitive

actions of the Georgia Prison system to prevent

Imam Jamil’s contact with other prisoners and the

right to practice his religion during his

incarceration. Additionally, we will challenge

the retaliatory transfer from Georgia to a

supermax “no contact” prison without his having a

federal charge, conviction or sentence. We are

very concerned about the impact solitary

confinement has on the physical and mental

condition of an inmate. [So, specific factors

being challenged in the retaliation lawsuit

include the imam’s 23-hour per day lockdown in

Reidsville, the violation of his religion rights

within the Georgia prison system, and the

gratuitous transfer to the Florence Supermax. –editor]

Challenge to the Prison Litigation Reform Act

The State has refused to settle our legal mail

case; therefore, we are preparing for trial. In

doing so, we first are challenging the Prison

Litigation Reform Act (PLRA). Our position is

that a constitutional violation is sufficient to

win punitive damages, just as a physical injury

entitles one to punitive damages. Courts are

divided on this issue. [The PLRA, as it stands,

prevents Imam Jamiland others in his

positionfrom receiving punitive damages for

violations such as the opening of his legal mail

in his absence, on the grounds that the damage

inflicted was not physical. –editor]. Our case

will give the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals an

opportunity to rule on this issue.

Q: What is the situation with Otis Jackson, the

self-confessed shooter in the crime for which

Imam Jamil was convicted?

A: Our attorneys have deposed Otis Jackson. His

testimony, that he committed the actions for

which Imam Jamil was convicted, has been

consistent. So, we’ve made some headway, but it’s

taken a long time. One of the reasons the State

said Otis couldn’t have done it, is that he was

wearing an electronic monitor. We talked to the

maker of the monitor and learned that it is

possible to beat the monitor. And in fact, he had

a faulty electronic monitor.

Part of the habeas has been that Otis was not

investigated. The prosecutor told our attorneys

“Oh, he’s crazy, like the other ones,” and the

attorneys froze and did nothing to investigate

the confession or the monitoring device.

Q: Any final words for New Trend readers?

A: Imam Jamil was previously incarcerated [under

the COINTELPRO era prosecutions of Black, Native

American, and other leaders and activists

–editor] for five years. He got out in 1976.

Right after the 2002 conviction, the prosecuting

attorney for the State said, “After 24 years, we

finally got him.” This confirmed Imam Jamil’s

position that it was a government conspiracy. Our

immediate short-term goal is to have the Imam

transferred back to Georgia, or to a federal

prison within a 500-mile radius of his home. Our

ultimate goal, naturally, is to exonerate Imam

Jamil. We thank you for supporting Imam Jamil and

our efforts to exonerate him.

---

Donations for Imam Jamil’s defense may be sent to:

The Justice Fund

P.O. Box 115363

Atlanta, GA 30310

Write to Imam Jamil Al-Amin:

Reg. No. 99974-555

USP Florence ADMAX

P.O. Box 8500

Florence, CO 81226

For more information, contact:

thejusticefund [at] aol [dot] com

No comments:

Post a Comment