Concrete Solitaire: A Poor Imitation of Death

by Enceno Macy

On June 19, 2012, Senator Dick Durbin held the first ever congressional hearing on America’s excessive use of solitary confinement. “America has led the way with human rights around the world,” Durbin said. But “what do our prisons say about our American values?”

“Solitary confinement makes our criminal justice criminal … It dehumanizes us all.” (Statement by Anthony Graves, exoneree who spent nearly 18 years in extreme isolation for a crime he didn’t commit.)

These are the conditions in which some 80,000 inmates live on any given day in American prisons and jails.

The light is as dim as a 40 watt bulb in a basement, like you might see in a B-rated horror movie. But this light illuminates a different kind of horror.

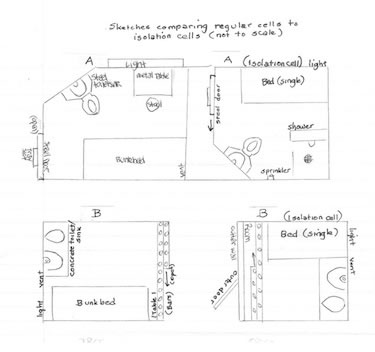

Imagine you’re in a cube, a concrete cube six feet by ten feet max. A thick concrete slab three feet high is built into the back wall. An exercise mat lies atop the slab, three inches thick and almost as hard as the slab itself. A stainless steel combination toilet-sink is built into the side wall, and next to it is a solid steel door. There may or may not be a small, filthy window, no bigger than a VCR tape, high up in one wall. The available floor space is about the same as a standard 4 x 8 sheet of plywood. This is your entire world, 24/7.

You have two books, if you’re lucky, chosen from a very limited selection of dog-eared novels, usually with subjects of no interest to you. A couple sheets of paper, a pen the size of a golf pencil, a toothbrush and a comb complete the inventory of your property.

Three times a day, a slot in your door opens, a tray is shoved through with strictly regulated portions of alleged food the FDA may or may not have approved strewn across it. Every two days, you are restrained — put in handcuffs and leg chains — and taken to shower. The hotel-size bar soap is made with the most basic ingredients, the major one probably lye, leaving your skin instantly dry. So dry that scratching the resulting itch tears your skin.

Occasionally you will receive your mail if the guards don’t ‘lose’ it and if you are fortunate enough to have anyone care enough to write to you. Every little noise echoes. Even the silence echoes, a dry, empty silence, the kind where you can hear yourself think. As months go by, the thoughts you hear become actual voices. After years in the cube, those voices become someone else’s and you no longer have a voice of your own.

This is a cell in what they call “segregation.” It used to be called solitary confinement, but for some bureaucratic reason it was changed to “segregation,” with various adjectives added. The use of solitary, once a relatively rare means of isolating prisoners whose violence jeopardized both guards and other prisoners, is now so frequent and so commonplace in U.S. prisons that prefab concrete segregation cubes are standard units of prison construction.

It is not hard to see how difficult it would be to keep yourself from going crazy in such a cube. Now add the probability — actually the strong likelihood — that most of the people put into those cubes already have some serious psychological problems before they are put there, and even a ten year old could deduce that such treatment would compound whatever problems someone had. Yet for the last 25 years, there has been a vast expansion of dungeons full of cubes like those I describe in prisons throughout the U.S. And their original purpose of keeping dangerous prisoners from harming others has been vastly expanded to include punishments for violations of prison rules and any behavior deemed insubordinate by sadistic or control-freak guards.

To anyone who has endured the horrors of solitary, it is impossible not to view this kind of punishment as an extreme form of cruelty. I would say cruel and unusual, except that it’s no longer unusual because every prison in the country has isolation units just as bad or worse than my description.

In some prisons, you are put on a leash when you exit the cell for any reason, like for medical treatment if you’re lucky. You are allowed to exit for “yard” once a week, for an hour alone in a slightly larger concrete cube with a screen across the open roof twenty feet above. This is your only contact with the outdoors. I have done a total of some two years off and on in solitary cells such as these. Not one of the experiences was anything but depressing and painful.

Logical thinking might lead one to conclude that lock-up, which is pretty much a long-term ‘time out’ from society, is not an adequate means of deterring criminal activity, especially when you herd a bunch of wildly dysfunctional people together and expect them to change. Of course it’s not; you might as well herd wild horses into a corral and expect them to change into dressage champions. I think actually addressing and correcting convicts’ issues would be more productive, but there is too much political and economic pressure hindering the introduction of rehabilitative services. An unempathetic society chooses to punish offenders instead of helping them, even if the punishment creates worse monsters than the originals.

For example, if you put a 15-year-old kid in prison for a lengthy amount of time (as I have been), and offer him little or no avenue to learn how to be a positive contributor to society, he will inevitably learn from what he is being exposed to. He will come to know only how to cope and survive in a locked-up environment surrounded by seriously messed-up guys. So when you eventually re-introduce him to society, what expectation can you have of him? Even if he tries his best to fit in, his reactions to situations will be a product of what he has come to know.

I have written before about the prison environment. It is 99 percent negative and sub-primal. This doesn’t mean no one ever survives it and returns to society to become a functioning citizen, but the likelihood of this happening is slim to none.

The same and more so can be said of locking someone in a solitary/segregation cube and expecting him to come out any better. The overwhelming likelihood is that he will emerge a far more violent, far more uncontrolled, far angrier person than ever before. Punishment may be a necessary aspect of deterring certain behaviors, but I don’t think people who have not experienced this kind of punishment can comprehend how it can actually harden one to the prospect of such consequences.

When you get put into that kind of isolation, you have no choice but to accept it. After a time, some people actually come to embrace the solitude, and it becomes a great discomfort to live in the general population again. Now they are not only no longer deterred by the threat of solitary, but are likely to create the situations that will send them there.

Around the country, some of these seg (solitary/segregation) units hold people for years, even decades, prolonging and eventually preventing their potential recovery from such an experience.

Cell extraction sounds like having a tooth pulled, but it’s nowhere near so benign. Say you refuse to return your meal tray through the slot, or as often happens you give in to the bottomless rage of despair and plug your toilet or flood the unit by leaving a tap on. Then you refuse orders to back up to the cuff-slot in the door with your hands behind your back to be hand-cuffed so the guards can enter and punish you.

What happens next is that six or eight officers in full riot gear with gas masks on charge the unit. They spray gas (pepper spray, or OC, which stands for ‘Oleoresin Capsicum’) into your cell, wait for you to succumb to the gas, and rush in. They slam you to the ground and beat you, zap you, then carry you to the showers before dumping you back into the same gas-filled cube, naked except for a bar of soap and a spray-soaked blanket. (A vivid and gruesomely accurate description of such extractions can be found in David Baldacci’s novel, Divine Justice; be aware that his account is most assuredly not an exaggeration.)

A cell extraction occurs almost every day, sometimes more than once. With 70 cells on one isolation tier, there is bound to be at least one disgruntled or insane inmate a day who can no longer stand the solitude. The officers have a field day with their gear and pepper spray. On at least one occasion they ‘accidentally’ set off an entire canister of spray, which made its way into all of the vents and into all of our cells. They wouldn’t let any of us rinse in the showers, so we endured the gassing for the rest of the night. It was so bad that a couple of guys passed out and had to be taken to medical. My neighbor’s nose would not stop bleeding; it gushed for hours until they finally came and threw him into the showers.

So far, the longest I’ve done in seg was 96 days. During that time the unit I was in set a state record for the most cell extractions in a single day, a total of 86. Such extractions, although common policy, do little to deter future negative behaviors. The only reason I never subjected myself to extraction, even during my less enlightened days, is that I am not fond of undue pain and would rather not pay the $200 (or more) fine that comes with it, along with a doubling or tripling of the time I would spend in seg. (When you consider that the usual prison job might pay you thirty dollars a month at best, you can see what an impossible debt that $200 is, since all your pay and any money your family sends will be commandeered until it’s paid off, and you don’t work or get paid anything while you’re in seg.)

Since most of these guys have little or no ability to anticipate or consider consequences in the heat of the moment, the Department of Corrections makes thousands of dollars in such fines — those 86 extractions brought in $17,200 in one day — taking advantage of inmates’ inabilities instead of helping to cure them.

Long-term seg units give inmates ‘packets’ that they are required to complete prior to release back into general population. These are basically a joke. The packets ask inmates to explore their behavior in an attempt to get them to understand how their thinking and actions led to their being in solitary. But there are no simple cookie-cutter answers to such complexities.

These inmates have spent their whole lives becoming who they are; a year or more of solitary confinement cannot alter the mentality that has been created during a lifetime — except to enhance the most negative elements of it. I mean, think about it: the very last things you’re likely to acquire while locked alone in a concrete cube are empathy or civil behavior or social conflict-solving techniques.

I am not an expert, so I can not propose satisfactory solutions to the dilemma of holding criminals accountable and at the same time avoiding any contribution to their mental and behavioral instabilities. A few things come to mind, though, primarily the need to help these guys understand the importance of becoming educated. Services using former prisoners, who are more likely to be regarded with respect and attention, could teach inmates this importance and provide opportunities to pursue all kinds of knowledge and skills, which would give them an incentive to stay out of trouble and to better themselves.

This would fill another important need: our need to feel useful and have something to do good for. Those who have been discarded by society — unloved, unwanted, uncared for — need this above all: a way to acquire or regain that sense of worth. Burying us alive in concrete cubes has exactly the opposite effect.

What society has done is invest in more and more solitary confinement cubes that intensify the problem, instead of investing in the education that could cure or prevent it. Somewhere I read that it is cheaper to send someone to Harvard than to incarcerate him for a year. That says it all, doesn’t it?

If the above looks like hell for an adult, consider please what solitary confinement does to a child, who has no experience or knowledge of how to survive such isolation. Children, by definition, are dependent on others — parents, teachers, siblings, friends, neighbors, bus drivers, whatever — for their emotional and intellectual development and stability. Take all those contacts away, and the child becomes feral and loses all incentive and ability to behave appropriately.

I know. I was fifteen years old when I was arrested, and spent eight months alone in a solitary confinement cell while awaiting trial. Another child locked in solitary summed it up grimly:

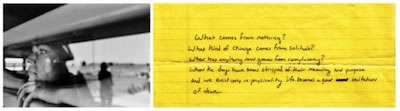

What comes from nothing?Trapped in that cube, I forgot what sunlight and fresh air were. I was allowed one book a week, a golf pencil and two sheets of paper a day. The term ‘driving me up the wall’ is an exact description of what it felt like. I spent a lot of hours crying because I didn’t know what to do with my thoughts. I didn’t know what my emotions were, much less how to deal with them. I did the only thing a kid with my limited emotional experience can do: directed my negative emotions into relentless hate and disdain.

What kind of change comes from solitude?

When has anything new grown from complaining?

When the days have been stripped of their meaning and purpose

And we exist only in physicality,

life becomes a poor imitation of death.

This molded me into a scared, hateful, angry person, which I never was by nature, drugged into compliance by jail staff. By the time of my trial, I had given up any thought or hope of being anything else. How such a human wreck could be expected to participate in his own defense is an abiding mystery. In this condition I was convicted and sent upstate, where my continued erratic behavior led to more and more time in solitary for breaking prison rules or mouthing off to guards.

I hated seg, and still do. But that never deterred me, because by the time of my trial and for years afterward, I simply didn’t care any more.

Note: Finally the issue of solitary confinement and its abuses is gaining some national attention, thanks largely to the efforts of Solitary Watch: News from a Nation in Lockdown, which has been collecting the voices of prisoners in the hole and recently took our voices to Congress for the first ever hearing on the subject. Stay tuned for further developments.

No comments:

Post a Comment